REGIONAL FOCUS

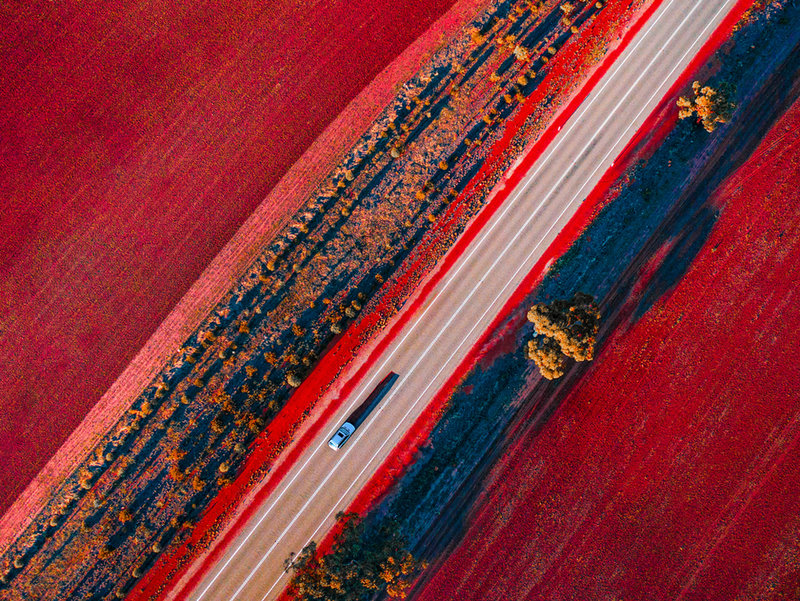

Navigating a hard border: spotlight on mining in Western Australia

The Chamber of Minerals and Energy of Western Australia recently raised concerns that an additional 8,000 skilled workers will be needed over the next 12 to 18 months in the resources industry. Scarlett Evans reports.

S

ince April this year, Western Australia has maintained a hard border in a bid to combat the spread of the coronavirus outbreak. Such a move has indeed proven successful, as it was one of the first states to declare zero cases and resume daily life, yet the decision to extend this hard border until the rest of the country sees the same result has led some to question how its minerals sector will remain afloat during this uncertain time.

Mining is not only the backbone of Western Australia’s economy, but of Australia as a whole. As such, ensuring operations can continue relatively unabated is crucial to offer some hope in the nation-wide economic downturn in the wake of the pandemic. But what does this actually mean for the sector? And where does it leave fly-in fly-out (FIFO) workers, who typically provide a significant portion of the workforce for major projects?

The hard border problem

While the pandemic has seen devastating knock-on effects for a multitude of industries, mining has been weathering the Covid-19 storm relatively unscathed, and the Chamber of Minerals and Energy of Western Australia’s (CME) warning for potential hiccups in sourcing workers seems to be only in service of keeping this fact steady.

“While CME members endeavour to recruit locally wherever possible, they have also made it clear that their workforce needs for the next 12 to 18 months cannot be met in full from within Western Australia,” says CME CEO Paul Everingham. “CME modelling suggests an extra 8,000 skilled workers will be required by the mining and resources sector over that timeframe, including some specialists who will have to be recruited from outside the state.”

According to Everingham, gold, nickel, lithium, and iron ore projects throughout the state will contribute to this need, with operations including BHP’s South Flank, Rio Tinto’s Koodaideri, and Fortescue’s Eliwana and Iron Bridge mines.

CME modelling suggests an extra 8,000 skilled workers will be required by the mining and resources sector.

“The estimated percentage of workers who would need to be sourced from elsewhere is small,” Everingham adds, “but their contribution to these projects will be vital.”

In response to this anticipated gap in the mining market, CME has said it is in discussions with the Western Australia Government, the Western Australia Health Department and Western Australia Police about adapting testing and quarantine laws for FIFO workers - angling for more lenient regulations that would enable greater ease of travel for such workers.

Another option under consideration is incentivising workers who fly into Western Australia to remain there.

Keeping miners in-state

Professor Rebecca Cassells from the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre says that mining companies and the Western Australia government alike are pushing to make relocation an attractive offer to typically transient workers.

“The current policy and building bonus is likely to draw currently engaged FIFO workers from the east to west coast and actually set up a home here,” she says. “Of course there’s a financial and emotional cost as well for workers, but there could also be some benefits. For instance, reducing the time these workers have to spend travelling could be great for mental health reasons. I think that's one of the reasons that the McGowan government has extended the building bonus grant to FIFO workers currently on the east coast wishing to actually relocate.”

Indeed, BHP has already made moves to encourage its interstate FIFO workers to make permanent moves west, giving preference to Western Australia job applicants and offering financial assistance for interstate employees - something that has already resulted in 800 employees moving to Western Australia.

While the initiative has its benefits, Cassells says maintaining a level of mobility between the states should not be sidelined.

We want to see a policy that will protect the industry, and the communities that these industries operate around.

“The key outcome we should be looking for [in] the sector is making sure that there is still a degree of labour mobility between the east and west coast,” she says. “Of course sometimes we can retrain locally, but a lot of the mining jobs are quite specialist.”

Regardless, the primary incentive to keep mining afloat seems to be to ensure Australia’s economy does not experience long-term damages.

“Even though we're seeing that the global economy has been taking a huge hit, mining has been quite protected,” Cassells says. “So protecting workers, companies, and the mining sites these workers are in is incredibly important.”

“Ultimately,” she adds, “we want to see a policy that will protect the industry, and the communities that these industries operate around.”

Supporting mining in Western Australia

Given the increased need for mining to keep the Australian economy grounded, it is unsurprising that upcoming projects are actually on the rise in Western Australia. In addition, a new government decision is working to streamline approvals and cut delays for new projects, ensuring the state is not simply operating as normal, but in fact increasing productivity.

Speaking with Matt Shackleton, managing director and CEO of Australian Potash, he emphasises that while there is a focus on getting projects up and running, it is by no means a rushed job.

“I wouldn't in any way, shape, or form characterise that as cutting corners, because that's not what's happening,” he says. “What's happening is they're getting through the important things on time. So we're not getting hung up on unnecessary bureaucracy. In my personal experience, this just means our approvals processes have gone according to schedule, which is really very positive.”

Iron ore’s powering and gold’s powering and nickel’s powering.

The sudden boom in projects is not without its own problems, and the bid for more production is causing something of a strain on resources, even without the issue of Covid-19. That is, even though projects may be going through approvals faster, there’s something of a bottleneck for the next stage.

“Iron ore’s powering and gold’s powering and nickel’s powering,” he says. “Because of that, you see a lot of the engineers, hydro-geologists, geological consulting firms, and even down to environmental consultancy exceptionally busy, and so as a result we’re seeing some fairly extended timelines. It's not so much the hard border thing there, but it's more about the fact that we're going through a real purple patch in resources at the moment, which is creating a bit of restriction in availability.”

While resources may be stretched at this crucial time, mining in Western Australia does not seem to be in danger of slipping. As a result, while we may be living in uncertain times, the sector continues to provide relative stability for not only the state, but the country as a whole.