Feature

With phosphate mining, the threat of displacement returns to Kiribati

Australian mining company Centrex’s phosphate exploration in Banaba has islanders worried that their homeland will be destroyed again. Ashima Sharma writes.

“Ocean Island Mine” at Sydney Opera House, on the plight of Banaba islanders. Credit: Michael Quelch via Getty Images

Australian mining company Centrex signed a phosphate exploration agreement with the Banaba islands’ administrative body in August, bringing back the threat of forced displacement to the island’s original inhabitants.

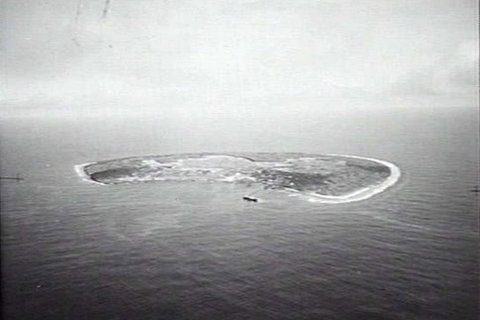

Banaba is the westernmost island in the archipelago country of Kiribati, in the Pacific ocean. Years of phosphate strip-mining had rendered the island uninhabitable, driving out its residents to Rabi, an island in Fiji. But, some 300 residents have returned since.

Through the 20th century until 1979, this 6km² island was rapidly mined for phosphate, used in fertilisers, stripping bare about 90% of the island’s surface. The Pacific Phosphate Company, jointly controlled by Australian, British and New Zealand governments, distributed the profits of mining 22 million tonnes of phosphate between 1900 and 1979, which went towards Australia’s agricultural growth.

Now, the residents want Centrex’s agreement revoked. Centrex director Robert Mencel said the company followed the due processes by seeking approval of the island's administrative body, the Rabi Council of Leaders. Locals dispute the statement, claiming the council’s funding was slashed by the Fijian military junta over a decade ago and has not been fully operational since.

Banaba in 1945

The council currently has just one representative, Iakoba Jacob Karutake, appointed by the Fijian government. He approved the deal with Centrex.

“The potential return to mining on Banaba, ironically, provides a much-needed catalyst for its potential rehabilitation and this is why the Rabi Council of Leaders has agreed to Centrex’s proposal,” Mencel said in a statement.

He continued: “Our objective is to demonstrate that significant remnant phosphate remains on Banaba that can be economically mined to satisfy increasing global demand for high-grade phosphate and at the same time, potentially fund the rehabilitation of the island.”

Phosphate and plundering on Banaba

Arthur Ellis, a young geologist at the Pacific Islands Phosphate Company in Sydney, arrived in Banaba in the year 1900. On an island then inhabited by 450 people, Ellis recognised the phosphate rocks and arranged for the locals to collect them, purchasing them for 4 shillings at the time.

To have exclusive and continued access to this abundant phosphate deposit, the British government annexed the island in 1901. Banaba then became a part of the British Gilbert and Ellice Island Group, getting a formal-yet-exploitative arrangement to mine the island for £50 per year for the next 999 years.

Over the next few years, the island of about 450 people became a mining settlement of 3000 Banabans, along with other indentured labourers coming in from Japan and China. This made Banabans a minority group in their own land. The British government then enjoyed a monopoly in phosphate mining there for three decades, until Japanese forces invaded in 1942.

Relocating yet fighting for their homeland

After the WWII, most families in Banaba were relocated to the Fijian island of Rabi. A diaspora of 6000 Banabans now live there in four main settlements that replicate the names of the four main villages of Banaba.

Addressing this influx, the Fiji colonial government passed the Banaban Settlement Act that provided a new administrative structure to the Banabans in Rabi. It called for the formation of an island council to act as the local government.

Phosphate mining destroyed or contaminated caves that held fresh water, making the place completely uninhabitable.

Banabans had historically survived periods of drought on their island because of the presence of natural caves that stored freshwater. Phosphate mining destroyed the majority of these caves and contaminated the rest, making the place completely uninhabitable.

The locals made many legal attempts to reclaim their land and receive compensation for the damage, leading to inconsequential wins. In 1976, a Banaban group sued the UK for its role in plundering the island; the court ruled the country had no legal obligation in the case.

While the British government made an offer of A$10m on behalf of all partner governments, it came with the condition to drop any further legal action, a term the islanders could not tolerate.

The future of phosphate contracts on Banaba

The current 300 residents of Banaba, keenly aware of the island’s previous destruction, have reasons for concern with the Centrex deal.

Karutake, the Rabi administrator who decided on the deal with Centrex, said an "exploration exercise" had been initiated to determine the remaining phosphates on Banaba, adding that the “exploration exercise is different from mining.”

Despite reassurance that landowners will be consulted for information and approval of the mining prospects, locals opposed the deal, and Karutake said the exploration will be put on hold awaiting further consultation with the community. While delaying the project is a successful push in the interim, the chairman of Tabweva village told The Guardian: “The agreement is still there, we want it torn up. That’s our land… and we have to protect it.”

Depleted phosphate fields in Nauru. Credit: Tim Graham via Getty Images

Katerina Teaiwa, an academic of Banaban Heritage at the Australian National University, told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation: "At the moment, all we've ever known is that our island was mined… and a lot of other countries got a lot of money and a lot of prosperity out of it.

"No real proper alternatives have been given to people about their future."