OPERATIONS

Mining companies face moment of reckoning

"Desecration" is a word no one wants levelled at them. For mining giant Rio Tinto, it’s one it has heard a lot in recent months. Some of its actions in Australia have been widely condemned and resulted in the departure of senior executives. Andrew Tunnicliffe dives into the damage done by the scandal.

B

lasting at Australia’s Juukan Gorge by mining giant Rio Tinto sent shockwaves across the sacred Aboriginal site that reverberated across the country and the global mining industry. The company’s controversial expansion project resulted in the destruction of 46,000-year-old rock shelters and one of the country’s most important archaeological research sites, sparking international outcry.

“Just a few short years ago, Rio Tinto was considered to be an industry leader in Aboriginal community relations in Australia. That is no longer the case,” says James Fitzgerald, legal counsel and strategy lead at the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR).

The native title and cultural heritage specialist worked on the case on behalf of ACCR, a research and shareholder advocacy body engaging with listed companies, industry associations, and investors on how they manage climate, labour, human rights, and governance.

He believes that good social performance isn’t about kindness and charity, it’s good business. Fitzgerald continues that over the coming decade, Rio Tinto will need new projects to supply minerals demanded by the new economy. He believes that its actions at the site “squandered much of its hard-earned reputation and goodwill, essential to its acceptance by communities in Australia and around the world”.

Embarrassing, self-exculpatory whitewash

Mining is big business for Australia, accounting for four of the 10 most valuable exports – to the tune of $185bn in 2020. It is critical to the country’s economic health and sustainability.

Compounding condemnation of its actions, then Rio CEO Jean-Sébastien Jacques addressed the criticism with a series of “embarrassing” statements, says Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies for Australia and South Asia at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

In the months following the destruction, we were treated to the embarrassing, self-exculpatory whitewash.

“He was joking about it… Even the previous CEO Sam Walsh said ‘look, you’re totally out of line and you have to leave’. It was only then that he [Jacques] thought ‘oh boy, I'm being called out by my peers, maybe I should have checked my wording’.”

It is a view shared by Fitzgerald who adds: “In the months following the destruction, we were treated to the embarrassing, self-exculpatory whitewash.”

What happened at Juukan Gorge was a game-changer, says Buckley: “It changed the landscape for ESG [environmental, social, and corporate governance]. It's pretty rare that ESG has ever claimed both CEO and chair scalps before, and these were pretty big ones. It was also pretty much a first for Australia, that traditional rights have ever been considered; albeit after the event.”

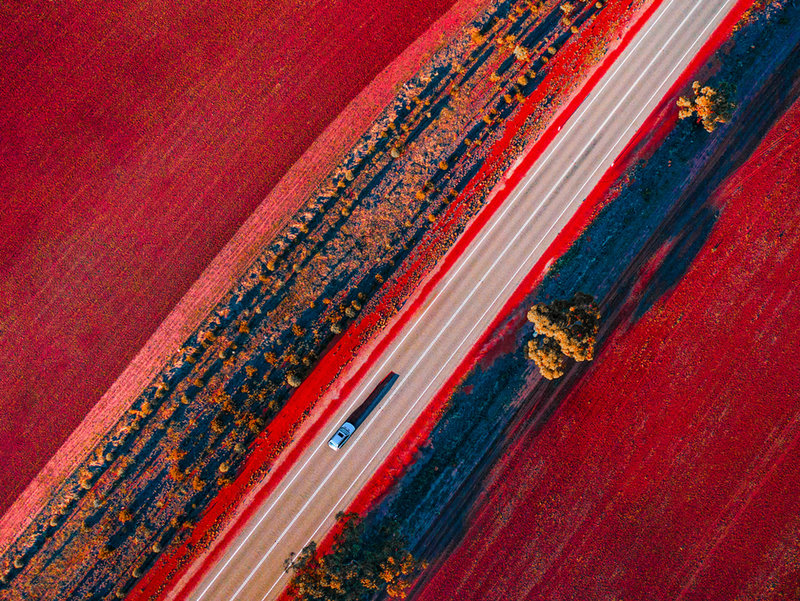

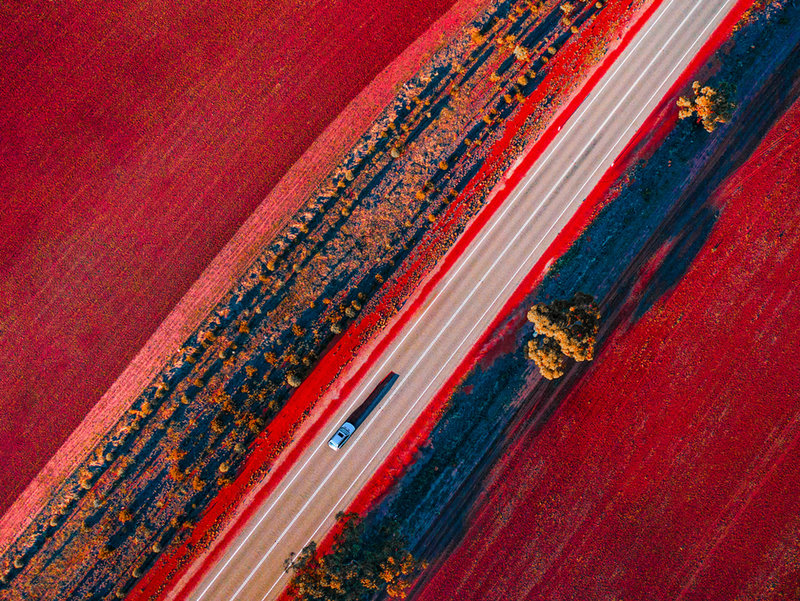

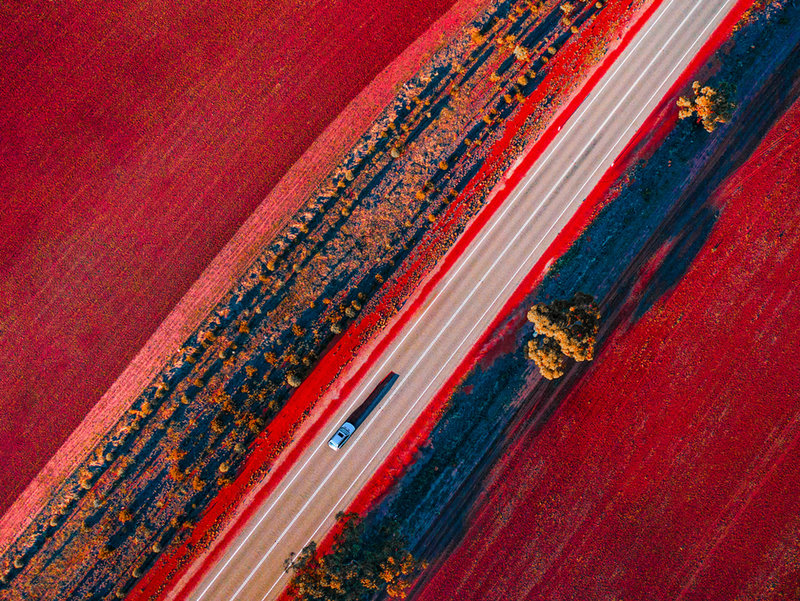

// Credit: Rob Bayer / Shutterstock.com

Executive departures and payouts

In September, Jacques and two other executives left the company as a direct result of its actions. However, that hasn’t ended the storm. Although all three received financial penalties – in Jacques case costing him almost $3.7m – none were stripped of their long-term bonuses.

According to some estimates, Jacques earned more than $13m in 2020 and departed the company, along with the other two execs, as “good leavers”. This meant pocketing around $37m in performance shares at the end of March 2021.

Speaking more generally about Rio Tinto and the mining sector, Buckley was scathing in his response: “I think one of the biggest issues is they've lost sight of reality, of what the average person actually earns. They've got their snouts firmly in the trough; they've failed to align the compensation of senior executives with the interests of shareholders.”

I think one of the biggest issues is they've lost sight of reality, of what the average person actually earns.

Rio has defended its decision to honour some of the executives’ financial packages. Speaking to shareholders, the company’s senior independent director and remuneration committee chairman, Sam Laidlaw, said that the board understood the sensitivity surrounding the situation and deeply regretted the destruction and the slow and initial “insufficiently sensitive” response.

He added that, to rebuild relationships with traditional owners and other stakeholders, changes of leadership had been required.

However, Laidlaw also said that the board concluded that it was not in a position to “legally terminate” the three executives for “cause and forfeit all outstanding remuneration”.

He added: “Instead, it was more appropriate that the three executives’ employment be terminated by mutual agreement, acknowledging the potential adverse effect that this may have on their longer-term careers.”

Shareholder revolt

However, at its recent AGM, says Fitzgerald, over 60% of shareholders – representing some $67bn at current valuation – rejected the board’s justification.

“All of these things point to a need for further cultural reform, from board level down. Among other things, the company needs to end its fascination with, and reliance on, disingenuous public relations solutions and get back to concentrating on real performance and good practice,” he says.

Their golden parachutes were beautifully silk lined and painless, and sinecures will follow.

The company says that it has listened and responded to criticisms relating to the events of last year. However, scepticism surrounding its conduct remains today. The shakeup of the board has stemmed some of the unrest, but it has not yet resulted in a rebuilding of trust.

“They [Rio Tinto] put their greenwash caps on and ate a bit of humble pie, for about a day. But have they really refreshed the board and senior management?” asks Buckley.

“There's no repercussions. They'll [former execs] fly in their private jets to private island holidays, whinging about how badly treated they were. But seriously? They weren't held accountable for their actions, they were rewarded on the way out; their golden parachutes were beautifully silk lined and painless, and sinecures will follow.”

Can restructuring bring change?

Fitzgerald goes further, questioning whether the restructuring can really bring about change. He believes that early indications about the new group CEO, Jakob Stausholm, are generally positive; he’s seen to have a genuine commitment to steer Rio Tinto back to an acceptable course and is taking good counsel.

However, much of the post-Juukan restructuring and re-staffing appears to have been designed by two people who have since left the company, both with close links to the former leadership and viewed as “part of the problem”.

Of particular current concern is Rio Tinto’s apparent reluctance to engage closely with national Aboriginal leadership in Australia.

“It remains to be seen whether the recent restructure has the necessary ingredients of right leadership, right systems, and right people,” Fitzgerald says. “Of particular current concern is Rio Tinto’s apparent reluctance to engage closely with national Aboriginal leadership in Australia. This was a hallmark of the company’s approach for decades and seems to be missing from the new approach, at least so far.”

Rio Tinto would argue differently. Speaking earlier this year, Stausholm committed to making cultural heritage an issue for the company, saying he wanted it “felt in the hearts and minds” all that represent it. He added the new executive board “feel very accountable” to ensure that something like Juukan Gorge doesn’t happen again and accepted that changes needed were not simply at a procedural level.

The global landscape of ESG

Today there remains a lot of unease regarding Rio Tinto and its competitors, both in Australia and around the world, in relation to the way they operate. The industry is being challenged to do what’s right, by stakeholders, lawmakers, and the general public alike; and so it should according to both men.

“The destruction of the Juukan Gorge Caves shouldn’t really have been a revelation to anyone because desecration of Aboriginal cultural heritage is a routine, work-a-day activity in the mining industry and has been for decades. Cultural heritage destruction is an integral part of mining in Australia,” says Fitzgerald.

However, the events of 2020 have at least served one purpose.

It's pretty hard for boards to ignore ESG now.

“I think it actually changed the global landscape of ESG profoundly,” says Buckley, “It's pretty hard for boards to ignore ESG now.”

Fitzgerald agrees, saying that ignorance is no longer an option: “If there is any upside to this tragedy, it is seeing investors and the public waking up to how Australian mining companies make their profits and dividends.”

Of course, that sentiment is particularly focused on the Australian mining industry, but it must not be mistaken for a regional problem. The sector’s rare earths, lithium, silver, copper and so on are crucial to future low-emissions economies and innovation. This, however, must be balanced with environmental and cultural needs. Whether companies like Rio Tinto are truly ready for change remains to be seen, but change is coming.