INSIGHT

Shattered people, shattered reputation: inside the Petra Diamonds human rights abuses

Petra Diamonds has had its reputation as an ethical miner broken by a lawsuit showing human rights abuses at its Williamson mine. JP Casey investigates.

I

n November 2020, UK-based NGO RAID drew the world’s attention to a range of human rights abuses at the Williamson diamond mine in Tanzania. Illegal miners were subjected to physical beatings, fatal assaults, and detention “designed to degrade, and in some cases, to amount to torture,” according to RAID’s report, with local security firm Zenith receiving much of the blame for the violence.

Yet this human tragedy has had far-reaching impacts for the global mining industry, with the mine’s owner, UK-listed Petra Diamonds, receiving criticism for its role in the violence.

Whether the miner’s owners were aware of the abuses and permitted them to continue, or were simply unaware and unable to stop such violations from taking place, the company has agreed to pay close to $6m in compensation to those affected, following a legal case helmed by human rights lawyers Leigh Day.

The incident highlights many of the challenges associated with an international industry like mining, where the global nature of operations means that local contractors are often relied upon to manage operations beyond the oversight of their partners. Beyond that, the case demonstrates the stark differences between a company’s stated ambitions, and its ability to meet its own standards in practice, and highlights that more can always be done to protect human rights at mine sites.

Human rights abuses and legal action

The Williamson mine is a project with a storied history. Responsible for producing the Williamson Pink diamond, owned by Queen Elizabeth II, and boasting an annual production of nearly 400,000 carats as recently as 2019, the mine is one of Tanzania’s most productive and profitable enterprises.

However, the mineral wealth of the region has made it a target for illegal mining operations, and since Petra purchased a controlling stake in the mine in 2009, illegal miners and security forces have clashed frequently.

People were being kept there, sometimes for days at a time, were being beaten up, were being denied food or humiliated.

According to RAID’s reporting, seven deaths and 41 assaults have taken place at the mine since 2009, and Petra’s own investigation, conducted in the wake of the lawsuits, drew similar conclusions. Petra has reported that between 2012 and 2020, there were more than 7,100 incursions of illegal miners onto the miner’s land, leading to over 1,700 arrests.

Petra noted that the majority of these conflicts were resolved “peacefully”, but there was evidence of violence from both illegal miners and security forces, including the jailing of a security guard in 2014 for shooting a miner, and the arrest of a second guard in 2016 for replacing their rubber bullets with stone or metal projectiles.

“People were being kept there, sometimes for days at a time, were being beaten up, were being denied food or humiliated, and were being detained, in effect, by private actors, operated by the company,” explains Anneke Van Woudenberg, RAID’s executive director.

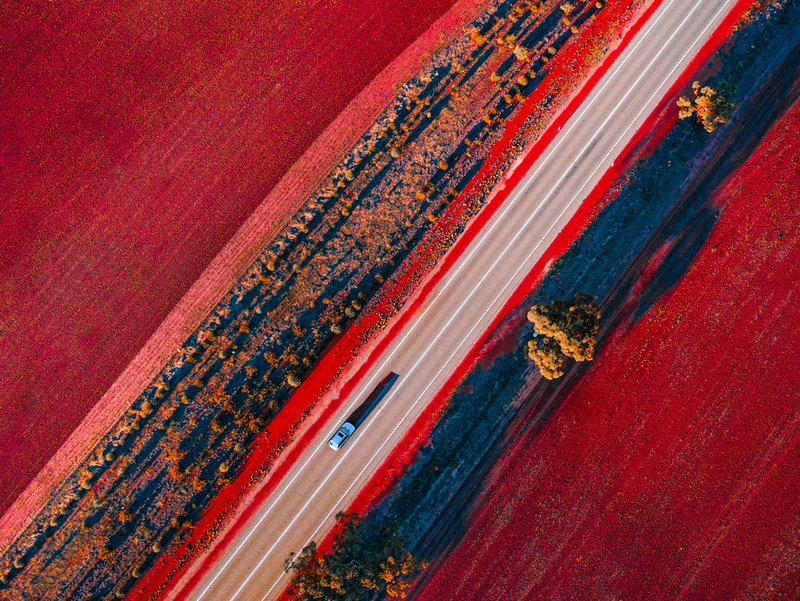

// Zenith security guards posing at Mwadui. Credit (all images): RAID

Detention centre operations

Woudenberg goes on to highlight how the mine’s storied past has left it with considerable infrastructure, which has been used to further abuse workers and locals. “We don't normally see detention centres operated by companies in this way.

“The second thing that was unusual in this particular case is that there was a hospital on the concession site, and some of the individuals they were detaining were then being picked up at night, dumped in a truck and they would then take them to the company controlled hospital on the concession.

“They were being handcuffed to the beds, being threatened, [and] told that they would only get medical treatment if they didn't talk about what had happened to them.”

They were being handcuffed to the beds, being threatened, [and] told that they would only get medical treatment if they didn't talk about what had happened to them.

In response, Leigh Day brought the complaints of 71 Tanzanian nationals to the London High Court and Petra agreed to a settlement that included financial compensation for the victims, the establishment of an “operational grievance mechanism” to track human rights abuses at the mine, and Petra’s involvement in new community projects over the next three years.

A further 25 claims are being investigated as part of the settlement, raising the prospect of further penalties levied at Petra in the future.

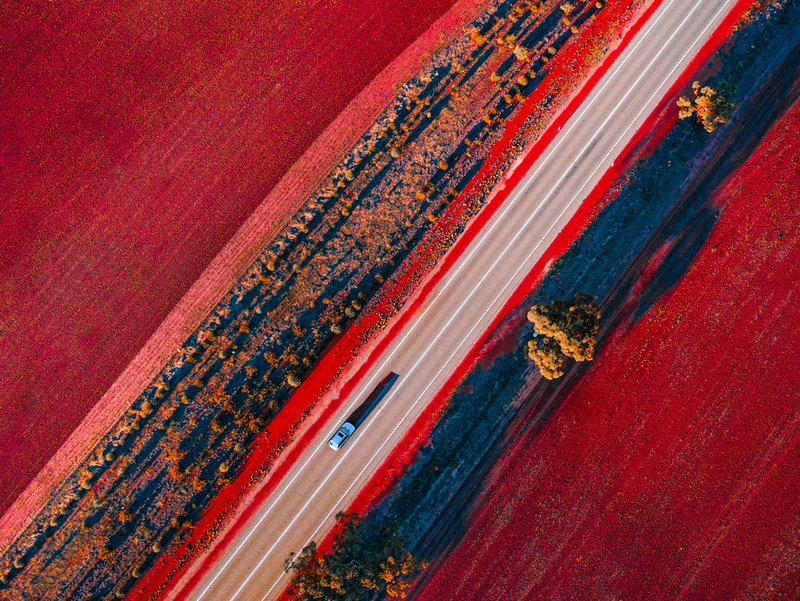

// Artisanal mining in the Kishapu District, Tanzania

A broken reputation

The incidents at the Williamson mine are all the more stunning considering the care with which many diamond miners conduct their operations, in order to avoid affiliation with issues such as conflict diamonds that have dogged the history of the mining industry.

“The diamond industry is an industry that really lives or dies by its reputation, selling a commodity that is very sensitive and that in the past has been linked with blood diamonds,” explains Van Woudenberg. “I think as an industry, the diamond industry is very aware about the marketing of diamonds and is very aware, in a generality, about the need to ensure that their product does not contribute to human rights abuses, and conflict in particular.”

The diamond industry is an industry that really lives or dies by its reputation.

“That's different than many other industries,” Van Woudenberg continues. “The knowledge about the need to really check one's supply chains and to check the origin of where your product comes from and to check to make sure your product is not contributing to any kind of harm; this is an industry that has been at the forefront of that.

“So when we first received allegations that there were serious human rights abuses at the Williamson mine in Tanzania, I have to say, I found those interesting but thought 'likely to be a rumour, unlikely to be true’, especially because the stories we were hearing were quite shocking, [including] people being handcuffed to hospital beds.”

// George Joseph Bwisige, leader of a group seeking compnsation for abuses at the mine

Petra’s ethical ambitions

Petra in particular has taken steps to establish itself as an ethical diamond producer. The company is listed on the FTSE4Good Index, as a company with a positive track record of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) compliance.

It is also a founding member of the Natural Diamond Council, a trade body representing 75% of the world’s diamond production, which holds its members to high standards of legal and ethical practices.

The disconnect, therefore, between Petra’s stated ethical ambitions and the realities of its work in Tanzania is striking. Yet there is some optimism for the company’s future in the depth of the independent investigation Petra held into its conduct, and the apologies made by its leaders, which suggests that the miner is committed to improving its ethical standards.

The company, board, and management are greatly saddened and concerned by the findings of the investigation.

The company, board, and management are greatly saddened and concerned by the findings

of the investigation.

When approached for comment, Petra provided the following statement as part of a press release: “The company, board, and management are greatly saddened and concerned by the findings of the investigation and we all regret the loss of life, the injuries, and the mistreatment of illegal diggers that the investigation has found to have taken place,” said Petra non-executive chairman Peter Hill.

“The actions being put in place, combined with the agreement reached with the claimants, are aimed at providing redress and reducing the risks of future incidents occurring. This is in keeping with our approach throughout, where we have tried to provide fair remedy, in the interest of all parties, based on a detailed, balanced, and independent understanding of the allegations made.”

Systemic challenges

Perhaps the conditions that allowed these abuses to take place are simply a sad consequence of an increasingly global world. Petra has demonstrated an interest in ethical mining, but having to delegate day-to-day management of its assets creates a separation between those in one part of the world with ethical priorities, and those in another without.

Yet globalisation is nothing new, and the companies that are wealthy and successful enough to boast such international operations ought to be similarly influential enough to track the practices of its constituent parts. Petra reported gross revenue of $406.9m in the 2021 financial year, a 38% increase over the previous year’s figures, in spite of a 10% decline in diamonds recovered and a 34% fall in total tonnage of diamonds treated.

I don't think any of them should be able to say 'well we were slightly far away so we didn't know'.

“The reality is we are in this globalised world where businesses are global; look at Amazon, look at Google. I don't think any of them should be able to say 'well we were slightly far away so we didn't know'; part of the work of these companies is to know,” says Van Woudenberg, calling for such wealthy and influential companies to keep a closer eye on their operations.

“They know when production is low, they know when their product is substandard, they check when their profits are affected. So they should also be checking to make sure that they're not causing environmental harm or human rights abuses.”

Establishing systems to report abuses

Perhaps one of the main lessons to learn from these incidents is the importance of systems that can be used to report human rights abuses and violations, to help nip such problems in the bud, rather than letting them continue unchecked for a decade.

Petra’s commitment to compensation and support programmes is an encouraging start, and will hopefully address what Van Woudenberg points out is a significant gap in the diamond mining industry.

“What struck me about this is that even though this is an industry that is well versed in the need to look out for these pitfalls on human rights, companies like Petra did not have systems in place to check that their marketing spin had really trickled down through the company and that company practices and behaviours were indeed checking and verifying that those lofty aims were being enacted,” says Van Woudenberg.

“The Petra diamonds case shows there was a major mismatch between ethical claims, and the reality on the ground. That should really give cause for concern to, especially ESG investors but frankly, any investors ... because Petra promoted itself as an ethical company that ESG investors should invest in, because they were doing the right thing on diamonds. They were ensuring their product wasn't marred by human rights abuses, and we found the opposite.”